The Hurricane of 1938

Check out this page for a map of all the tagged locations

Imagine it’s September 1938. It has rained 14 inches in the past week so the ground is saturated and rivers and streams are over flowing. Remember it’s September so the tide is high at the autumnal equinox (when both the sun and the moon’s gravity tug at the sea level). Take a look at the trees around, they still have all their leaves making each tree a full sail. Perhaps you’re listening to Boston meteorologist E.B. Rideout as he tells his WEEI radio listeners, to the skepticism of his peers, that a hurricane would hit New England. Perhaps you’re reading The Day’s forecast which just called for “rain and cooler temperatures with moderate shifting winds.”

Today is the 84th anniversary of the Hurricane of 1938. It’s one of the themes that shows up again and again when researching the history of parks all over the state. The storm, also known as the Great New England Hurricane, made landfall in Connecticut at 3:50 PM on September 21st, 1938. The storm left 700 dead and 63,000 people became homeless overnight. It damaged or destroyed nearly 20,000 buildings, 26,00 cars, 3,300 boats, and killed approximately 2 billion trees affecting 35 percent of New England’s total land area and causing $620 million in damages (only something like $13 billion today, although a lower-grade modern storm like Hurricane Sandy cost an estimated $60 billion in a much more dense 2012 population).

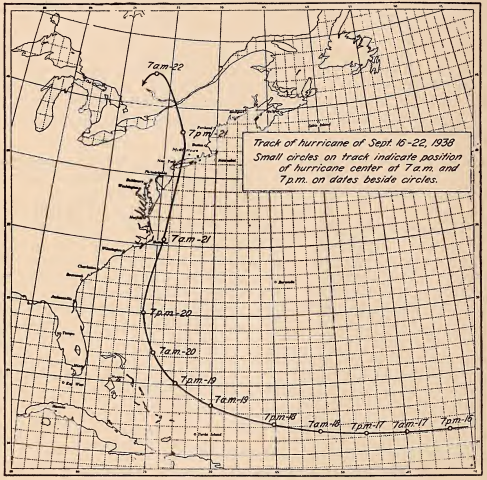

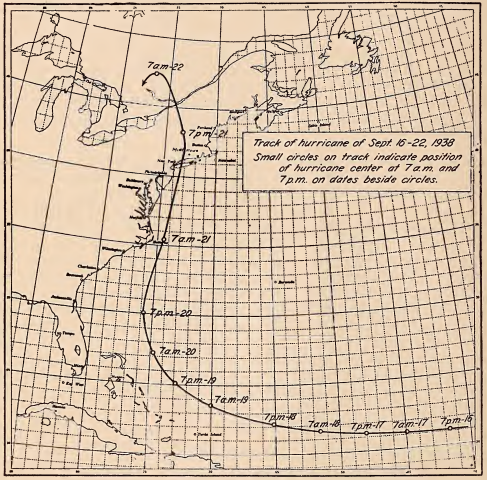

The storm started 500 miles off the coast, almost leisurely making its way towards the eastern shore-board of the United States over the next four days. Experts predicted that it would curve out to sea and spend its power in the mid-Atlantic. Hurricane tracking had been started by Father Benito Vines in Cuba at the Royal College of Belén as early as the 1870s. The US Government became involved and continued to develop the tracking and warning systems for the next 30 years, but it wasn’t until the 1920s that even rough predictions began to be made and it wasn’t until 1954 that we got real statistical forecast models of hurricane paths.

As the storm neared the coastline on the evening of the 20th it was caught between two high pressure systems which guided it up the coast and fed its ferocity, tripling its speed from 15 mph to at least 47 mph. It passed near Cape Hatteras at 7AM on the 21st as it continued to gain speed. A bit later it glanced off the New Jersey coast near Atlantic City damaging resorts and cottages and showing that the storm had covered over 600 miles in just 12 hours at that point.

In Connecticut, thanks to persistent September rains the ground was soaked and rivers like the Connecticut were overflowing. The state had gotten 14 inches of rain in the four days prior to the hurricane. The center of the storm hit the coast just to the west of New Haven at 3:50 PM carry an ocean storm surge at high tide that destroyed coastal towns all the way out to the Cape. The eye traced a line towards Hartford passing it at 4:17 PM before curving slightly westward into Massachusetts, through Vermont, and into Canada by the evening when it was no longer destructive. James L. Goodwin noted that it struck his Pine Acres Farm (now Goodwin State Forest) around 2 PM and lasted for at least four hours, dropping another 4 inches of rain.

Picture sustained winds of 45mph with gusts from 87 to 121 mph. 100 of thousands of trees in the state were snapped or uprooted over the course of the storm, estimates say that half of the larger conifers and one-fifth of the larger hardwoods east of the Connecticut River were felled as a result and as many as 3 billion board feet of timber was salvaged in the aftermath. James Goodwin alone was able to sell 91,218 board feet of wood from trees on his property to a government-run timber salvage corporation. That’s about 17 miles of boards, more than enough to lay down a board across every one of Goodwin State Forest’s current trails including its section of the Air Line Trail. Many more trees fell across streets and roads, carrying down telephone wires, breaking down buildings and fences, and uprooting great masses of earth and roots carrying with them sections of sidewalk.

At the time there were 38 state parks, 20 state forests, and the blue blaze trails were 8 years old with at least 400 miles of trails.

George Utter of the CFPA Trails Committee said in the aftermath,

“If you could see what I have just seen, your heart would bleed with mine. More than 40 miles of Narragansett Trail have gone with the hurricane. Thousands of great trees lay mangled where they were tossed. I did not believe any such thing could happen over an entire area.”

Bob Ohler of the Appalachian Mountain Club recounts that longs stretches of the Appalachian Trail were impassable as well,

“I tried to descend the trail the day after the storm with nothing but my ax. By nightfall, I had only made it through three quarters of a mile down the trail.”

Austin Hawes, then Connecticut State Forester said,

The wind literally pushed over whole acres of these trees as though a great hand had slowly but inexorably swept over the land, leveling everything before it. Sometimes the wind pushed the trees only part way over and they now lean at a sharp angle.

Basically every state forest lost plantations of their oldest red and white pines. Beautiful old stands of hemlocks along Mashamoquet Brook were completely blown down as were much of the hemlocks at Devil’s Hopyard State Park. The entire stand of white cedar at Pachuag State Forest was leveled. Yale had just set up their forestry camp in Eastford in 1934 and it too was completely wrecked.

For coastal parks, the grand pavilion at Hammonasset faced extensive damage from storm surge. At the time there were over 100 shacks and cottages on Bluff Point known as the Bluff Point Colony. About 80% of the summer resort community was swept away and one wonders if it would still have become a state park 25 years later hailed as one of the ‘largest undeveloped stretches of land on the Connecticut coast’. Similarly at Silver Sands State Park, the area was a filled in salt marsh built over with beachfront homes, many of which were destroyed in 1938. The storm shares credit with Hurricane Diane in 1955 for destroying most of the rest and turning the area into a state park in 1960.

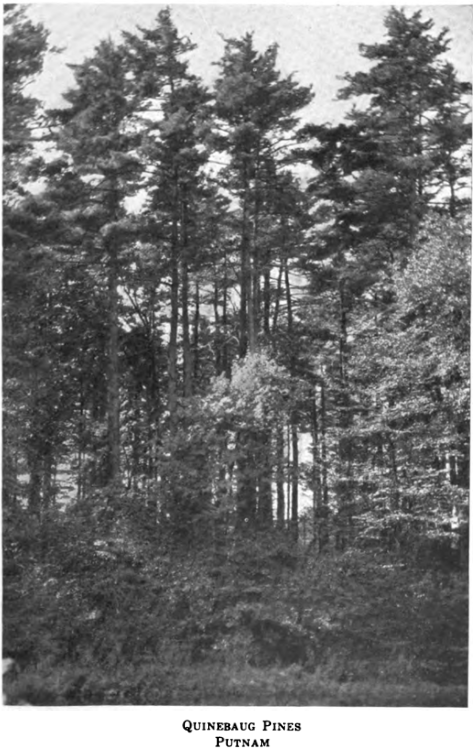

The 159 acre Shaker Pines in Enfield were destroyed. A former state park called Quinebaug Pines, located in Putnam, started with the purchase of 37 acres for $6,100 in 1923. The old stand of pines was one of the few remaining in the state at that time, with some pines at least three feet in diameter, and was used as a picnic grove on the river for many years. Damage was so bad that the state abandoned the property and ended up trading it to American Optical in 1948 for 24 acres along Lake Mashapaug which became modern day Bigelow Hollow State Park. And, at Penwood State Park, the hurricane damaged so much of the property that Curtis Veeder was so disheartened at the state of his forest retreat that he tried to donate it as a state forest before he passed away. His wife, Louise, donated it as a state park in 1944.

Flooding caused by the storm prompted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to begin studying the flooding problems in the Thames River Basin. They planned three dams for Connecticut located in Mansfield on the Natchaug River, in South Coventry on the Willimantic River and in Andover on the Hop River. Only the Mansfield project moved forward and ultimately led to Mansfield Hollow State Park 14 years later. A similar project came to fruition in the 1960s at West Thompson Lake after floods in 1936 and the hurricanes of 1938 and 1955.

Other work, like those done by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps starting in the early 1930s were damaged by the storm. A number of bridges were washed away by flooding like the one built by the men of Camp Fernow in Natchaug State Forest. It was rebuilt in the Fall of 1939 with steel i-beams and you can still walk over it today.

The men of the CCC camps were also deployed around the state clearing roads. 20 men from Camp Fernow spent 5 days just clearing the roads at Goodwin State Forest. The US Forest Service sponsored a request for 2,000 men to create Fire Protection work crews in Connecticut, but never got more that 400, largely because State, CCC, and WPA crews were already hard at work. The state was broken into 9 zones with the goal of clearing roads of branches to 50ft (leaving trunks for the property owners) and debris from around houses to 200ft. Some of the work took as many as 5 years to complete.

Smaller properties have anecdotal tales as well. Holt-Kinney Woods in Mansfield has a stand of pines dating back to the hurricane. Field Park in Haddam lost 50 of its largest trees including many ‘original exotic plants’. Ravines like the Illick parcel at Cockaponset State Forest and Bailey’s Ravine in Franklin seemed to funnel the wind knocking down old hemlocks in both.

All these tales of extreme damage remind me of the tornado that touched down in Meriden in 2018. Sleeping Giant and Wharton Brook both lost large stands of pines and I was shocked then at the open fields in both parks that remained after the cleanup, lamenting the loss of these peaceful groves. I extrapolate that incident across much of the state, picturing how some of my favorite spots could be forever altered over just the span of a couple hours. However, it’s also clear that the present state of many of my favorite locations might not exist at all without previous devastation 84 years ago. Mansfield and Bigelow Hollows might never have been created, the coastal parks might be completely developed with rich mansions, and the communities might never have rallied together seeking to not only recover but to improve what once was.

I find it meet and right to discover such heart in the wake of such damage, forests grow, communities build, and opportunity abounds.