History of Forestry in Connecticut

The history of Connecticut’s forests is the story of glacial setting, managed landscapes, their cultivation and preservation and of course raging fires, leveling hurricanes, and expanding blights. Interwoven are the people who brought Connecticut to the forefront of agriculture and forestry, pioneering the state forests, and setting the stage for the open space we enjoy today and for those who will inherit it in the future.

An easy starting place is the receding of the Ice Age about 20,000 years ago. Many view this as a destructive time – the scouring and crushing of rock underneath relentless pressure from the ice dramatically changing the landscape. But I like Robert Thorston’s view of ‘glacial gifts’. The fertile Connecticut River Valley, the numerous rocky waterfalls around the state, our iconic stonewalls, the Hanging Hills, the Metacomet Ridge and traprock are all gifts of the glaciers. But, before this becomes ‘The History of Geology in Connecticut’, the glaciers set the stage for what would come next – the forests.

As the conditions grew warmer cool climate pines like boreal conifers (aka spruce, fir, and hemlock) began to cover the eastern seaboard with Connecticut at the heart and shifting sand dunes interspersed with jack pine.

The gradual succession to hardwood deciduous forest (oak, maple, ash, alder) likely happened over and over again. Pollen records in our area from around 11,000 years ago indicate a change from a mixed hardwood forest back to a boreal (spruce, fir, larch, birch, alder). And 4,000 years ago hemlocks were nearly wiped out by some disease opening the canopy once again.

There were certainly people here then too. Archaeological work at the Lebeau Fishing Camp and Weir in Killingly documents artifacts indicating the presence of Native Americans here 8,000 to 6,000 years ago. Surely as skills increased there would have been camps for maple sugaring and tree-processing for canoe manufacture. Certainly by 1,000 years ago regular camps existed near Mamacoke Island and Selden Neck. The claim that the landscape was pristine and unmanaged even then appears to be a myth.

Of course many of us are familiar with the colonial era when trees were cleared for fields, rocks were moved to stonewalls, and forest coverage across the state dropped from over 90% to nearly 30% from 1600 to 1850. I always find it interesting to try to imagine what that landscape looked like on my hikes around the state. Largely open fields ringed by stonewalls and dotted by wolf trees, rocky ledges even more exposed and ripe for exploration, overlooks even clearer with views farther. Occasionally I even come across old accounts and descriptions when researching these locations and I find the change across time fascinating.

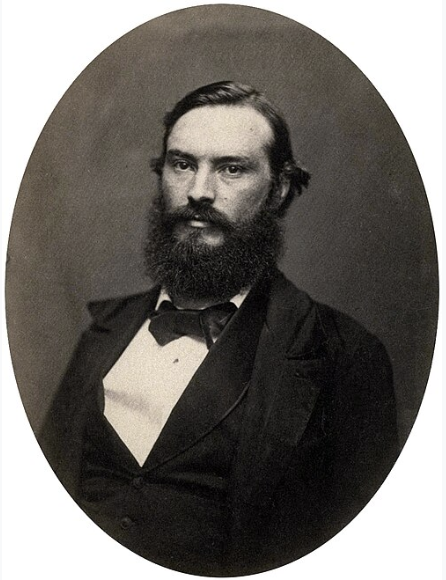

Here we join with the first ‘father of forestry’ in Connecticut. Not Gifford Pinochot as my History of Yale Forestry article might have made you think. Credit is given to William H. Brewer another earlier Yale professor who’s deep knowledge and leadership put Connecticut at the forefront of forestry from 1864 onward. At the time, forests were still more about the game they contained and the timber they could provide, and perhaps as in England for the recreational delight of princes and Kings. Brewer instead shifted thinking to forests as agriculture and of their (re)cultivation.

This provided the technical basis for forestry to become a science and the plantations that would be needed for experimentation. Forestry associations developed over the late 1800s led by men like Edward Bowers and Henry Graves (who would both go on to the Yale School of Forestry). And naturalists like Thoreau and Emerson had already been eloquently preaching the preservation of wild and park land. It is here that we meet again with Gifford Pinchot who focused the countries attention on forestry and later helped shift it to conservation. And it is here that the early Connecticut Forestry Association forms in 1895 seeking to “develop public appreciation of the values of forests and the urgent need for preserving and using them rightly”.

In 1901, this group facilitated the establishment of the first state forester position in the nation (the honor goes to Walter Mulford) and crafted a state forest acquisition policy, making Connecticut the first state able to acquire lands specifically for state forests.

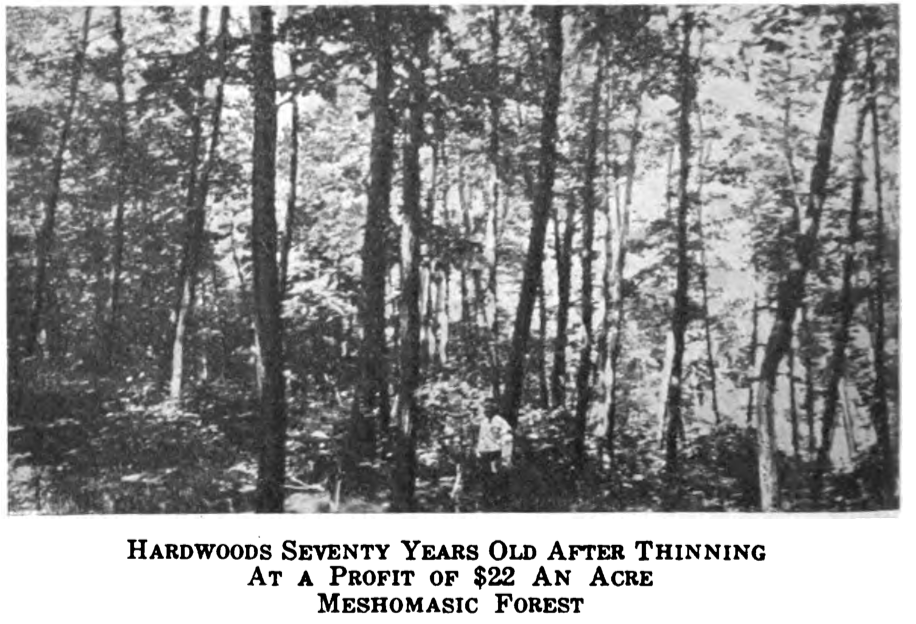

In 1903, Connecticut acquired its first 70 acres for $105 (only $3,535 in 2022) calling it the Portland State Forest (now known as Meshomasic State Forest). Unfortunately, it was only the second state forest in the country narrowly beat out by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania who had acquired land in 1898 for what is now Sproul State Forest.

As forestry science advanced at Yale and across the country, Connecticut expanded purchasing land for Union and Simsbury State Forests (now Nipmuck and Massacoe State Forests respectively). Austin Hawes, Connecticut’s 3rd State Forester, describes what it was like to visit Meshomasic in 1904:

“I was obliged to take an early morning train from New Haven to Middletown; then take a trolley which ran once an hour to Gildersleeve, the end of the line. There Del Reeves, the Caretaker of the Forest, would meet me with his old horse and buggy and we proceeded, at a pace never exceeding a walk, to his farmhouse, a distance of about four miles. We arrived there about lunch time, which in winter allowed only about three hours to look over the forest. Consequently, in order to accomplish anything three days were required for the amount of field work which can now easily be accomplished in one day.”

Hawes was state forester form 1904-1909 and again from 1921 to 1943. During this time he oversaw the surveying of Litchfield and New Haven counties, the planting of millions of seedling trees, the harvesting of hundreds of thousand of board feet timber, and the acquisition of nearly 80,000 acres of state forest.

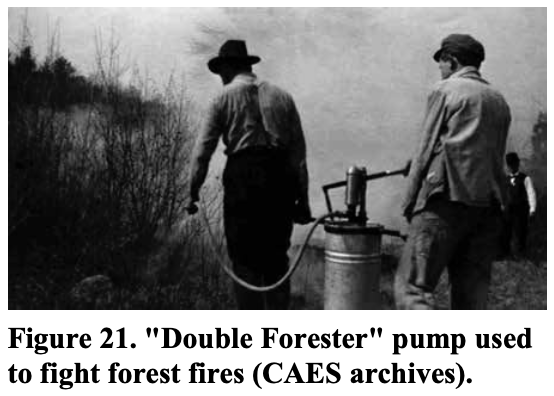

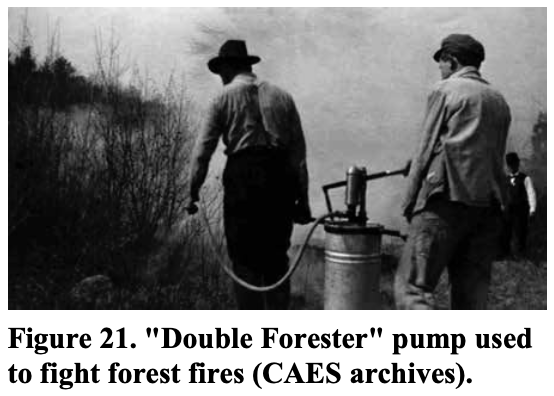

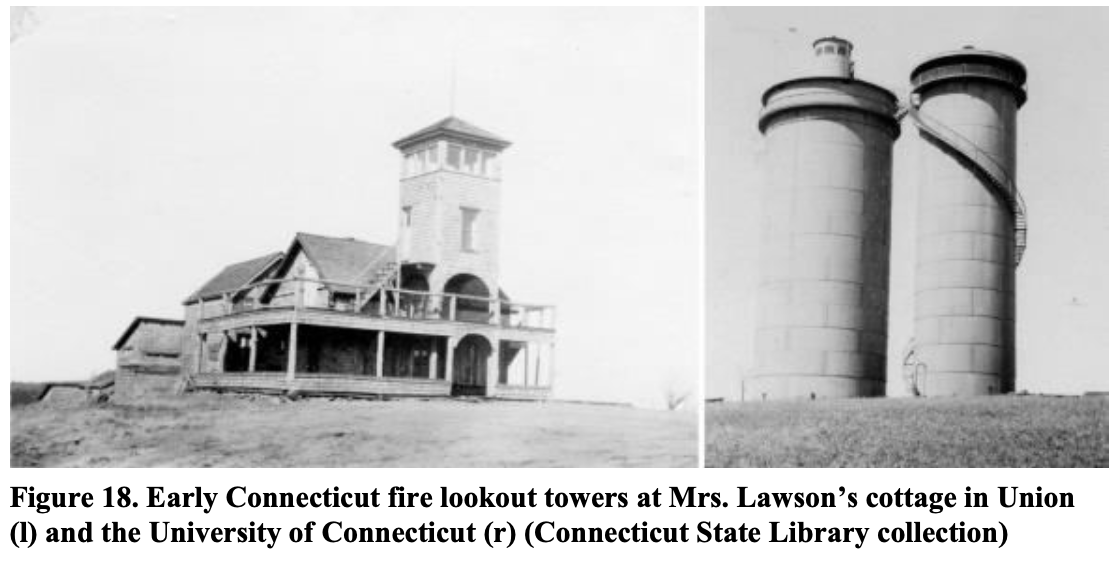

Forest fires, largely caused by railroad sparks, were an enormous issue in the early 1900s. Numerous articles and Hawes annual reports detail the up to 1,000 fires each year, the acreage destroyed, and their financial cost. In 1918 for example there were 889 fires burning 33,000 acres and causing $110,000 in damage. The land for today’s Massacoe State Forest had been burned so many times by the Central New England Railroad, which passed through it, that the owners considered it valueless and sold it to the State for $1.00 an acre. Techniques were tested, fire fighting technology was upgraded and a series of fire towers were erected to detect fires earlier many of which still remain today in locations like Mount Tom and Soapstone Mountain providing landscape overlooks and sunset views.

Of course natural disasters struck the forests – gypsy moths, who escaped from a French astronomer L. Trouvelot who had wanted to use them for possible silk culture around 1869 in Massachusetts devastated New England forests in the early 1900s. The state had terrible flooding in 1936 which led to several dam projects including Mansfield Hollow. There was also the infamous hurricane of 1938 which nearly leveled the entire state (but that’s a blog post for another day 😉).

The forests were also built up thanks to work done by the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and the men of the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) who had camps around the state building bridges, pavilions, and replanting forests. All of which led to a greater public awareness and appreciation of the outdoors and our natural resources. You can find plaques dedicated to the men of the CCC camps in a number of state forests and you likely have hiked trails they blazed or used improvements they made like the handsome old pavilion at Stratton Brook.

The state forests continued to grow well into the 1940s due to guiding hand of Austin Hawes and support from that Connecticut Forestry Association which had reincorporated in 1928 as the Connecticut Forest and Park Association who stewards the blue blaze trails and so much more today.

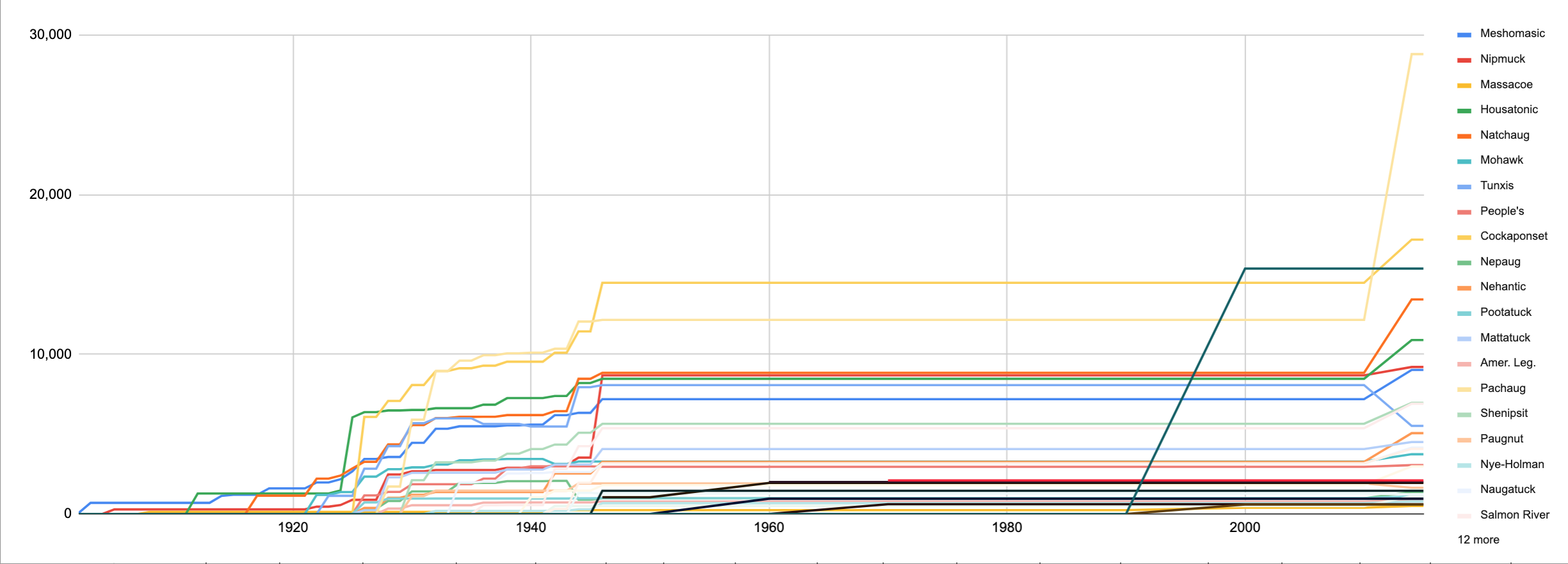

By 1950 state forests totaled about 110,000 acres, but over the next half century growth stagnated. I put together this rough chart to show the growth of the state forests from 1903 to the most recent data in 2015. You can see the long plateau starting around 1950 which is also in part due to paucity of data once the State Park Commission stopped their biannual reports. Thankfully, the growth of land trusts and town conservation commissions starting in the late 1960s started to preserve small parcels of forest for recreational use and today we rank among the top in the country for land trusts.

In 1997, the State of Connecticut adopted the goal of protecting 21 percent of Connecticut’s land area — a total of 673,210 acres and set a deadline of 2023. The goal was spearheaded by then Department of Environmental Protection Deputy Commissioner David Leff who had been partly inspired by New York City, who despite enormous population density, had 20% of its land in open space at the time. Around 1997 state forests amounted to at least 130,000 acres, the state had acquired 93 of its current 110 state parks, and land trusts and town parks had been in full swing for 30 years.

Despite this enormous head start state spending started to slow again 2005. Then the Great Recession depleted already meager finances slowing land purchases and grant programs like the Recreation and Natural Heritage Trust Program for state lands and the Open Space Watershed Acquisition Program for towns and land trusts. Thankfully we were still able to preserve forests like Mono Pond, but the big acquisitions were derelict properties like Sunrise State Park and Seaside State Park.

Now just a few short months away from that goal the state’s best estimates are 514,489 acres protected, or 76 percent of the goal. This counts all federal, state, town, utility, land trust, and private open space land. I still count this as amazing. As I detailed in my blog post ‘The Wealth Around Us‘ there’s a high chance you have hundreds of miles of trails just 30 minutes from your doorstep and 1,000s of acres of protected land. That 21% was certainly aspirational and adopting a metric like a certain number of acres might not be the best approach. As we’ve seen over this brief glimpse of our state’s forests it can be just as much about cultivation, protection, and improvement as expansion.

Today these half million acres are a vital core to life in the state. They provide habitat, purify air, filter water, prevent erosion, buffer development, and provide abundant recreational opportunities. From their humble beginnings as test tree plantations and fire fighting testing grounds, through their struggles against natural disasters and invasive species, to prime acres we’ve lost to development – our state’s forested open space is ours to enjoy and steward for future generations.